We applied the basic fishbone schematic to two systematic reviews that differed in key ways, so that we could illustrate the applications for various kinds of topics, patient populations, interventions, and outcomes. Each bone (representing an outcome) can include additional explanatory factors such as a plain language summary of the effect, the number of studies, the magnitude of treatment effects, or other factors that influence the certainty (strength) of a body of evidence.

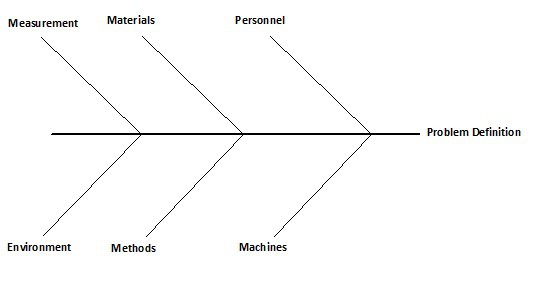

GRADE, for example, recommends ranking the relative importance of outcomes when developing guidelines. The proximity of the bones to the head reflects the importance of outcomes for decision making. The bones of the fish represent individual outcomes that are critical or important to balance the overall benefits and harms of the interventions. In our adaptation of the fishbone graphic, the “head” represents the overall balance between benefits and harms of an intervention or of competing interventions. Second, we summarize the results of a user testing exercise comparing a fishbone diagram with a GRADE summary of findings table.Ĭoncept of the fishbone diagram to summarize evidence of systematic reviews In the following sections, we first discuss the adaptation of the fishbone diagram using two real-world examples to show how systematic reviewers and others can use this graphical technique. Determining the best format of communicating risks and benefits of healthcare interventions is important because the correct interpretation of beneficial and harmful treatment effects is a prerequisite for informed decision making. Theoretically, such a graphical technique could help readers to comprehend the conceptualization of the review and complex findings through a simple, succinct, and understandable format. We envision that fishbone diagrams could be effective tools for improving informed decision making among readers of systematic reviews with little epidemiological training. In this manuscript, we explore the utility of fishbone diagrams to display the totality of a body of evidence with multiple outcomes. Fishbone diagrams could possibly fulfill this need. Currently no presentation tool exists that offers a less complex option than summary of findings tables yet more in-depth methodological information than fact boxes that summarize the best available evidence on the benefits and harms of treatments but are targeted towards patients. To our knowledge, fishbone diagrams have not been used to summarize the findings of health care research. Figure 1 presents a generic fishbone diagram.Įxample of a generic Ishikawa fishbone diagram (by Fabian Lange)įishbone diagrams also have been widely used in health care for cause and effect analysis related to patient safety, and for evaluating quality management processes.

#ISHIKAWA DIAGRAM TEMPLATE EXCEL SOFTWARE#

Software for constructing fishbone diagrams is available within general graphics packages such as Microsoft Visio (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) or in specific packages, such as SmartDraw© ( ), which provides more flexibility for drawing, modifying, and annotating fishbone diagrams. The diagram was first termed an “Ishikawa diagram” but was later dubbed “fishbone diagram” because of its resemblance to the skeleton of a fish-a horizontal spine with the “head” representing a problem or effect with the “bones” emanating at acute angles representing causes. įishbone diagrams were first proposed by Kaoro Ishikawa in the 1960s to display cause and effect in the context of continuous improvement of industrial processes. To address such limitations, a simplification of the content using graphical displays could provide an excellent approach for enhancing presentation to readers with limited epidemiological training. Nevertheless, to be interpreted correctly, summary of findings tables require familiarity with some concepts of clinical epidemiology and with grading the certainty of the evidence. They significantly improve readers’ overall understanding and their ability to find critical information compared with having data only in text. Summary of findings tables such as those proposed by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group, have become important tools to summarize results of systematic reviews and present the certainty of findings.

#ISHIKAWA DIAGRAM TEMPLATE EXCEL FULL#

Such tables are often dense and do not allow readers to grasp the findings “at a glance” but instead require review of numerous pages of summary tables and large parts of the full evidence report. The traditional approach to presenting such complexity is to develop multiple summary tables that describe the design of the studies, present results, and assess the quality of evidence. Systematic reviews gather, describe, synthesize, and evaluate evidence on a wide range of topics in health care, many of which are complex and multi-faceted.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)